After taking 2022 off for personal reasons, I have purchased my first (non-digital only) full series pass to my local film festival, SIFF2023. Over the 2 ½ week runtime of the festival, I watched 33 features and 1 short in person along with another 11 features and 5 shorts online as part of the virtual fest. In lieu of full reviews for all films (which would take me months), I wanted to share my quick thoughts on everything that I saw.

Past Lives (Dir. Celine Song)

As beautiful as it is made out to be, Past Lives explores the space between platonic and romantic relations. It ponders what could have been and romanticizes the past while accepting that the present reality can also be beautiful. For her first time behind the camera, Celine Song possesses a preternatural instinct for creating an emotionally devastating piece of cinema. The closing seconds of the film were some of the most tear-jerking seconds of cinema in recent memory. I left the theater ugly crying all the way to the after party.

★★★★★

Retreat (Dir. Leon Schwitter)

An inauspicious start to the first proper day of the film festival, Retreat was beautifully shot but lacking substance. A little character motivation from the father besides, “things are bad” would have gone a long way. The ending was significantly darker than I was expecting and left a bit of a bad taste in my mouth.

★½

Angry Annie (Dir. Blandine Lenoir)

In the wake of the overturning of Roe, a slew of abortion related historical dramas have come out. Angry Annie is a solid outing in that undertaking with a stellar performance by Laure Calamy as the titular woman. And while it falls a little to trap of telling over showing in its later moments, it’s still a wonderful timely telling of a story that needs to be told at this point in time.

★★★

King Coal (Dir. Elaine McMillion Sheldon)

A documentary on the cultural significance of coal to the Appalachia region, and the hole that the decreased reliance on the fossil fuel has on the people who live and work there. By focusing on a pair of young girls who are seeing the world around them change as quickly as they are, King Coal stays grounded in a unique perspective.

★★★½

The Night of the 12th (Dir. Dominik Moll)

The multiple César winning The Night of the 12th is an intriguing police procedural about an enigma of a real-life case. The film is well acted and keeps viewers on the edge of their seat as each additional ex-boyfriend appears more guilty than the last. While the film was very good, I don’t believe it lives up to the award winning hype.

★★★

The Eight Mountains (Dir. Felix van Groeningen)

The beautiful Cannes winner tells the story of two male friends who’s destiney is tied together in the mountains around where they met as children. The film had the best cinematography of the festival, but its two-and-a-half-hour runtime was longer than necessary and the film declined to end at many natural concluding spots.

★★½

Harka (Dir. Lotfy Nathan)

Harka was a very dark portrayal of poverty in Tunisia. Really strong design decisions stood out in this dirty drama. The filthiness of Ali’s (Adam Bessa) single shirt and construction zone turned one room home created the depressing tone for the film. The ending was exactly what it had to be, but the added surrealism to the moment sells the film.

★★★

Falcon Lake (Dir. Charlotte Le Bon)

Falcon Lake presents its traditional coming of age story as if it were a horror film. Editing and score decisions amplify this decision, and the horror aesthetic works well for the adolescent story as that time can feel like a horror movie at the time. The young Joseph Engel and Sara Montpetit put in solid performances and sell the mysteries of adolescence.

★★★★

Year of the Fox (Dir. Megan Griffiths)

A rough first outing with a really stilted screenplay and dialogue left this coming-of-age film feeling hollow. The voice over from Ivy (Sarah Jeffery) was exceptionally detrimental to the film. I unfortunately have very little positive to say about the film, but I know others enjoyed it so take that as you will.

★

Filip (Dir. Michal Kwiecinski)

With a stellar lead performance by Erk Kulm as the titular Filip at the center of it, Filip was a great WWII drama that focused on the life of a Jewish Pole living undercover in a Nazi occupied hotel. The film takes a unique look at WWI by focusing on the life of people livening under occupation but not in the camps.

★★★

And the King Said, What a Fantastic Machine (Dir. Axel Danielson)

A documentary about the power of cameras and media. And the King Said, What a Fantastic Machine is filled with intriguing imagery, though the message of the film gets a little blurred. The film becomes less about the power of the camera and more about the power of televised fascism.

★★½

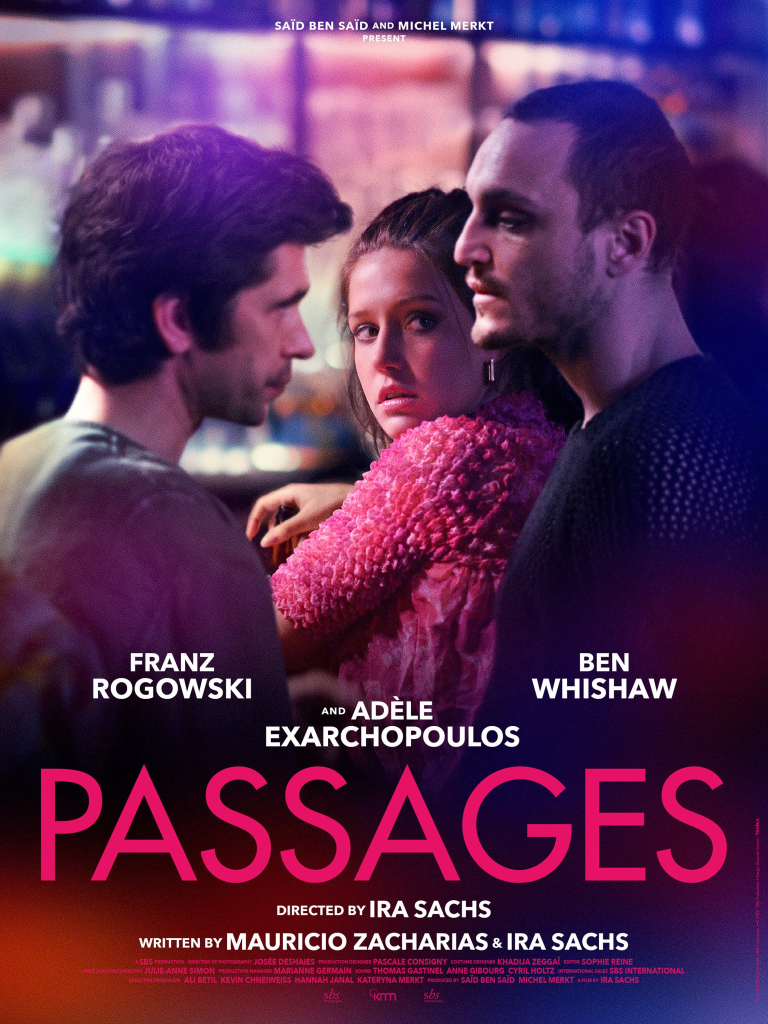

Passages (Dir. Ira Sachs)

Ira Sachs continues to be an enigma to me. I have wanted to like all his films, and I have never disliked any of them, but I have also yet to feel a real connection to one. Passages was no different, as the sex filled, love triangle drama was intriguing if not engrossing. The complexities of being a bisexual man exploring sex with women for the first time in years makes for a solid story; it just didn’t resonate with me.

★★½

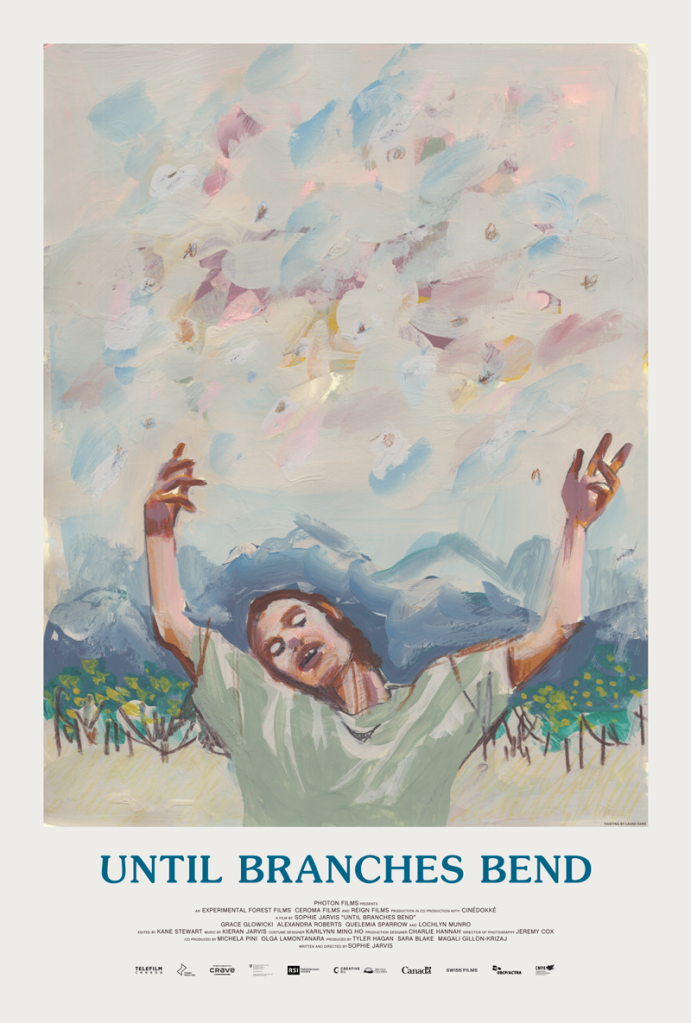

Until Branches Bend (Dir. Sophie Jarvis)

This Erin Brockovich story lives entirely on the lead performance of Grace Glowicki as Robin, a woman who finds a beetle inside a peach and creates an uproar over it. Glowicki is wonderful in the film, and she manages to encapsulate the uncertainty of the reality she lives in when the tow around her starts to gaslight her on what she saw.

★★★

Monica (Dir. Andrea Pallaoro)

The first of three trans related films I went out of my way to see explores a trans woman’s connection to her mother even years after abandonment. By staying hidden throughout her visit Monica (Trace Lysette) is allowed a small amount of closure, but the distance never closes in a way that hits close to home.

★★★½

A House in Jerusalem (Dir. Muayad Alayan)

A ghost story that isn’t scary and a pro-Palestine narrative that is completely buried, A House in Jerusalem misses the mark on most axes.

★½

Matria (Dir. Álvaro Gago Díaz)

Matria reminded me of a Dardenne Brothers film. A story of a working-class woman forced to endure extreme circumstances but still finds a way to preserver. The moments of joy she allows herself while the world around her crashes is the highlight of the film.

★★★½

Motherland (Dir. Hanna Badziaka and Alexander Mihalkovich)

Two very different documentaries combined into one messy one, Motherland firstly tries to tell the story of bullying in the Belarusian army, but through lack of access to any of the violent acts resorts to additionally focusing on a group of boys partying after being enlisted but before entering the army. The two stories don’t mesh and make for a confusing 90 minutes.

★★

The Blue Caftan (Dir. Maryam Touzani)

Breathtakingly beautiful, The Blue Caftan lives in closeups in soft focus of the three lead actors Lubna Azabal, Saleh Bakri, and Ayoub Missioui along with longing shots of the gorgeous fabrics and threads used to make the handmade caftans. What is obsessively a love triangle story is filled with love and adoration between all three characters. The Blue Caftan is destined to go down as one of the year’s finest films.

★★★★½

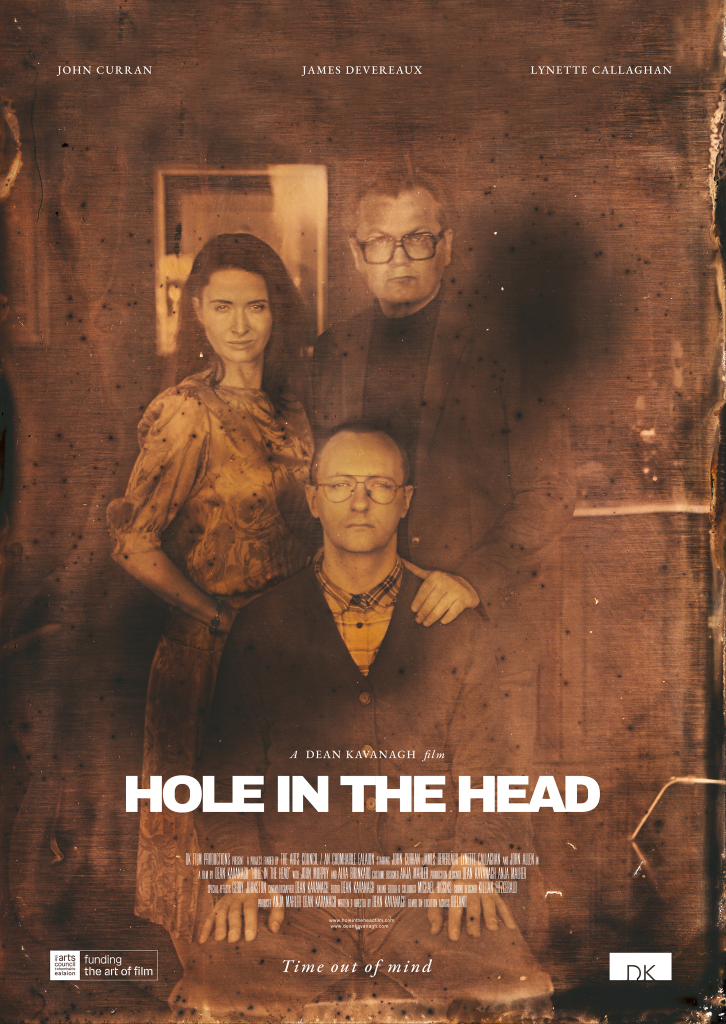

Hole in the Head (Dir. Dean Kavanagh)

My one walk out of the festival, Hole in the Head attempted to be Dean Kavanagh’s version of My Winnipeg, but without the style and skill of a Guy Maddin, the film rends itself unwatchable.

½

Next Sohee (Dir. July Jung)

The story of a young, South Korean woman who kills herself under the pressure of an externship at a call center and the woman detective who follows her case, Next Sohee plays out as two separate stories stapled together. While each are excellent on their own, the combining of the two was a little inelegant.

★★★

Confessions of a Good Samaritan (Dir. Penny Lane)

Penny Lane’s documentaries are always an enjoyable, highly stylized bit of fun and Confessions is no different. Her most personal film to date perfectly captures her neurosis as she goes through the process of donating a kidney to a stranger. Funny and well edited Lane continues to be a director to seek out.

★★★½

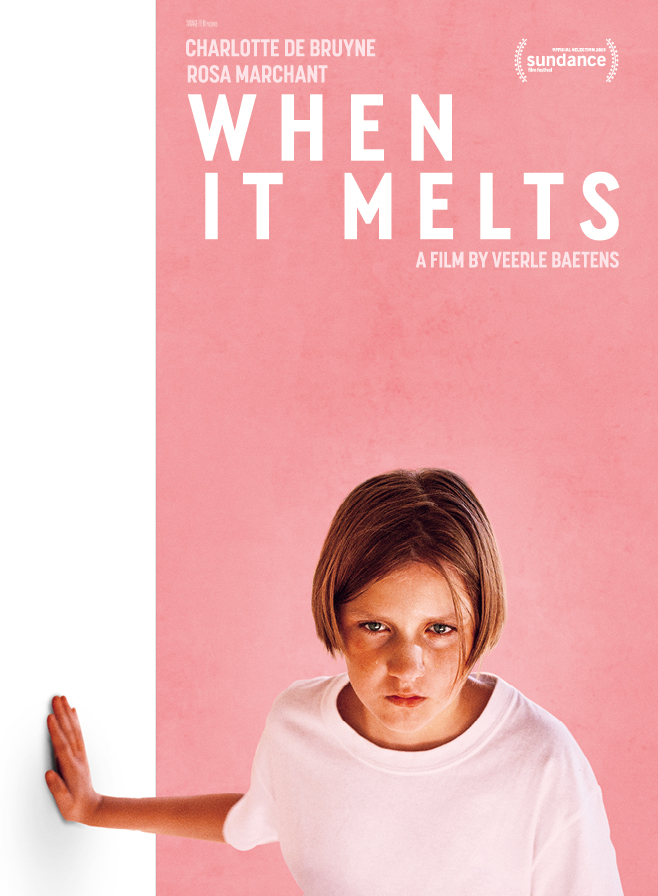

When it Melts (Dir. Veerle Baetens)

The darkest film of the festival, When it Melts explores the long-lasting effects of childhood trauma. By cutting back and forth between Eva as an adult (Charlotte De Bruyne) and a child (Rosa Marchant) Veerle Baetens tells a twisted story that can only end in one way and that way is devastating.

★★★

Other People’s Children (Dir. Rebecca Zlotowski)

A loving tale of a woman who becomes attached to her boyfriend’s young daughter; Other People’s Children is heartwarming. Virginie Efirais excellent asRachel the women in question, and her connection not just to the young Leila, but all the young people in her life make her the ideal mother just without a child of her own. My only complaint is that the film could have used another round of editing, the epilogue in particular either needed to be cut or more flushed out beforehand.

★★★½

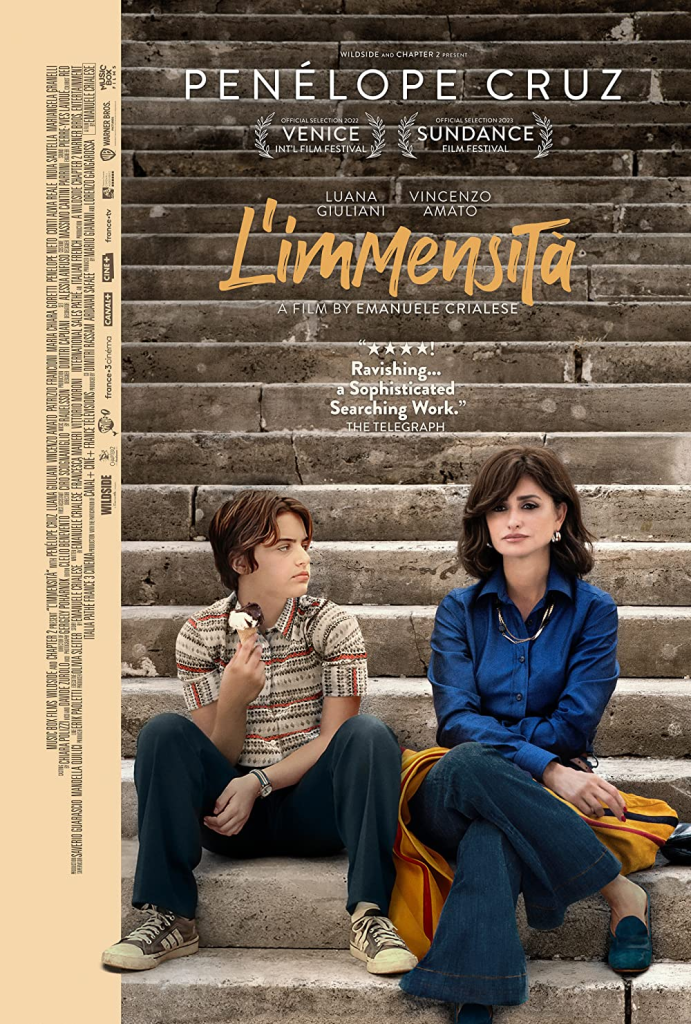

L’ immensità (Dir. Emanuele Crialese)

Penélope Cruz as the mother of a trans boy, what’s not to love? Unfortunately quite a lot as L’ immensità just didn’t quite hit. With three out of nowhere musical numbers, and an occasional glimpse into fantasy, this film didn’t know what it wanted to be and failed for that.

★½

Plan 75 (Dir. Chie Hayakawa)

Set in near future Japan, Plan 75 proposes a world where the elderly can choose to be euthanized to help remedy a society that has aged. Given that premise, the film explores it from three viewpoints, Michi (Chieko Baishô) a woman considering signing up for the program, Hiromu (Hayato Isomura) a man signing people up for the program, and Maria (Stefanie Arianne) a woman working at a facility. The film plays with the moral implications of the program in a way that doesn’t judge but makes you think.

★★★★

20,000 Species of Bees (Dir. Estibaliz Urresola Solaguren)

It may have taken me a few days to realize it, but 20,000 Species of Bees was my favorite film of the festival. Whether or not it is the best film of the festival may be up for debate, but nothing hit me personally. Estibaliz Urresola Solaguren manages to perfectly capture the mix of confusion and gender bliss that a young trans person experiences while figuring out who they are. Sofía Otero plays the 8-year-old Lucía beautifully. I’m starting to tear up just thinking about the film I love it so much.

★★★★½

Sonne (Dir. Kurdwin Ayub)

This film baffled me. It centered around an Iraqi teen Yesmin (Melina Benli) living in Austira. She and her friends do teen like things include making a viral video of them singing Losing My Religion by R.E.M.. Weirdly though the film introduces plot points throughout the film without ever following up on them. Near the end I finally started getting on board with the all vibes no plot follow through but it ended before I could entirely get it.

★★

Ernest and Celestine: A Trip to Gibberitia (Dir. Julien Chheng and Jean-Christophe Roger)

An absolute delight, the sequel to 2012’s Ernest and Celestine has just as much if not more heart. The bear and mouse pair get into more adventures in Ernest’s hometown of Gibberitia where music has been banned, and obviously that means the score and diegetic music are the highlights of the film.

★★★★

Let the River Flow (Dir. Ole Giæver)

Let the River flow is the tale of Ester (Ella Marie Hætta Isaksen), a Norwegian passing Sámi woman who embraces her indigenous identity to join a resistance against a dam that threatens Sámi land. A moving tale against colonialism and about finding power in who you are.

★★★½

Dreamin’ Wild (Dir. Bill Pohlad)

Bill Pohlad, the Love & Mercy director returns for another music biopic, this time about the Emerson Brothers. Headlined by Casey Affleck who is as sure a bet for a great performance as there is in Hollywood today, the film captures the unbelievable story of the two brothers as they learn their 30-year-old album has become one of the hottest tickets in the music industry.

★★★½

Blue Jean (Dir. Georgia Oakley)

Lesbianism in the era of Margaret Thatcher, Blue Jean tells the story of a gay gym teacher who while in a loving relationship finds the need to keep things hidden to keep her job. When she sees one of her students at the gay bar with her, she needs to balance being a good gay role model with protecting herself. This dichotomy is perfectly realized in the excellent film by Georgia Oakley.

★★★½

The Hummingbird (Dir. Francesca Archibugi)

The first half of The Hummingbird showed great promise from director Francesca Archibugi. The editing between timelines was seamless and orchestrated wonderfully to create a coherent story despite taking place in half a dozen eras. Unfortunately, the second half introduced more plotlines that were not as interesting, and the tight editing fell away.

★★½

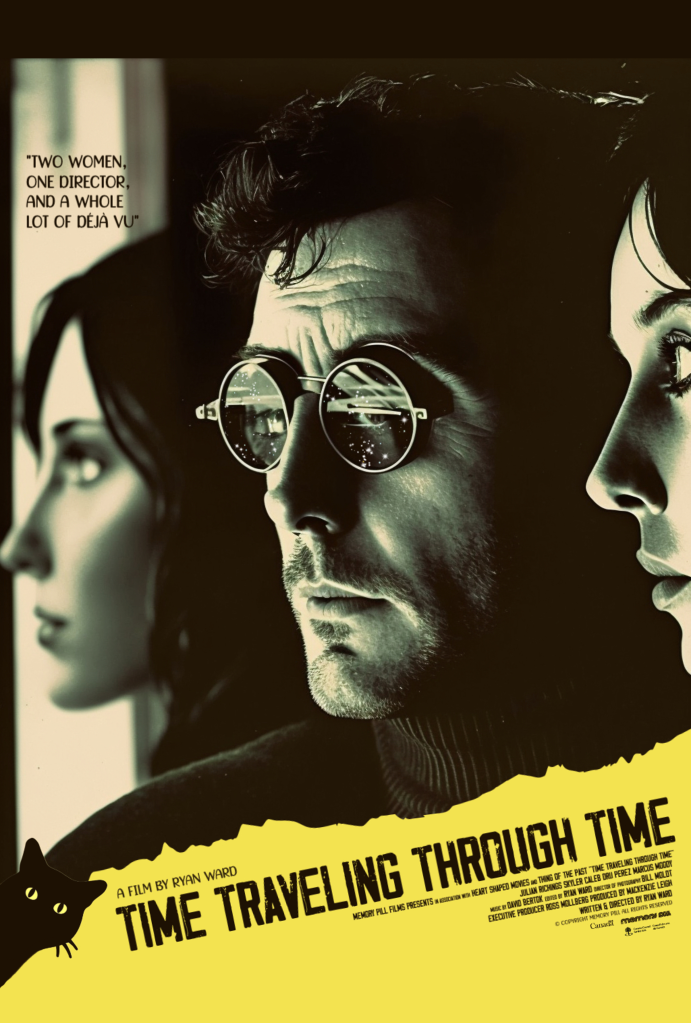

Time Traveling Through Time (Dir. Ryan Ward)

A comedic, short homage to Chris Marker’s La Jetée is more interesting in premise than in practice.

★½

LOLA (Dir. Andrew Legge)

My final in person film of the festival was a packed house to see this black and white science fiction. The women lead super geniuses who invent a form of time travel and use it to change the outcome of WWII was unique and a great while not the absolute best film of the festival was a fun way to close it out.

★★★

26.2 to Life (Dir. Christine Yoo)

Rehabilitiation stories are something I’m always open to receiving, and 26.2 to Life does a great job of humanizing the inmates at San Quentin State Prison. Christine Yoo uses the running program as a gateway to investigate the lives of the men who use it as an escape and a way to stay connected to life.

★★½

Satan Wants You (Dir. Steve J. Adams)

An intriguing documentary on the satanic panic scare and its source – The 1980 memoir Michelle Remembers, Satan Wants You as a rather cut and dry talking head documentary, but the subject matter is what draws you in.

★★½

Inglorious Liaisons (Dir. Chloé Alliez)

A unique depiction of teenagers (all portrayed by painted electric plugs and on/off switches). The short portrays what it’s like to be a closeted lesbian when everyone around you pushes you to get together with the cute boy.

★★★

Now I’m in the Kitchen (Dir. Yana Pan)

A very short sketchy animation about a woman remembering the impact her mother had on her through the catalyst of the kitchen.

★★★

The Voice in the Hollow (Dir. Miguel Ortega)

Very interesting art style, but a pretty bland story.

★½

Europe by Bidon (Dir. Samuel Albaric and Thomas Trichet)

A rather boring animated short of a man trying to immigrate to Europe.

★½

Pipes (Dir. Kilian Feusi, Jessica Meier, and Sujanth Ravichandran)

A very short, animated film of a bear fixing pipes in an underground gay club. Funny and sex positive.

★★½

Egghead & Twinkie (Dir. Sarah Kambe Holland)

Zoomer Scott Pilgrim but make it gay. I enjoyed Egghead & Twinkie substantially more than I thought I would. Not all the sequences worked as well as others, but it was still a fun coming of age story with a lot of style and a lot of heart. A great promise at what Zoomer cinema will look like.

★★★

Hanging Gardens (Dir. Ahmed Yassin Aldaradji)

What if Lars and the Real Girl, were about a very young Iraqi boy. That’s essentially the premise of Hanging Gardens where the young As’ad finds a sex doll and sells the use of it for money while slowly becoming over protective of his findings.

★★★

Bad Press (Dir. Rebecca Landsberry-Baker and Joe Peeler)

An eye-opening documentary about something I knew nothing about (the lack of freedom of press in most Native American territories). The film follows a story of one papers struggle after their nation repealed the freedom of press act.

★★★

Adolfo ( Dir. Sofía Auza)

Everyone wants to make the next Before Sunrise, and few people succeed. Adolfo is an overly quirky version of the trope does not end up as one of the better ones.

★½

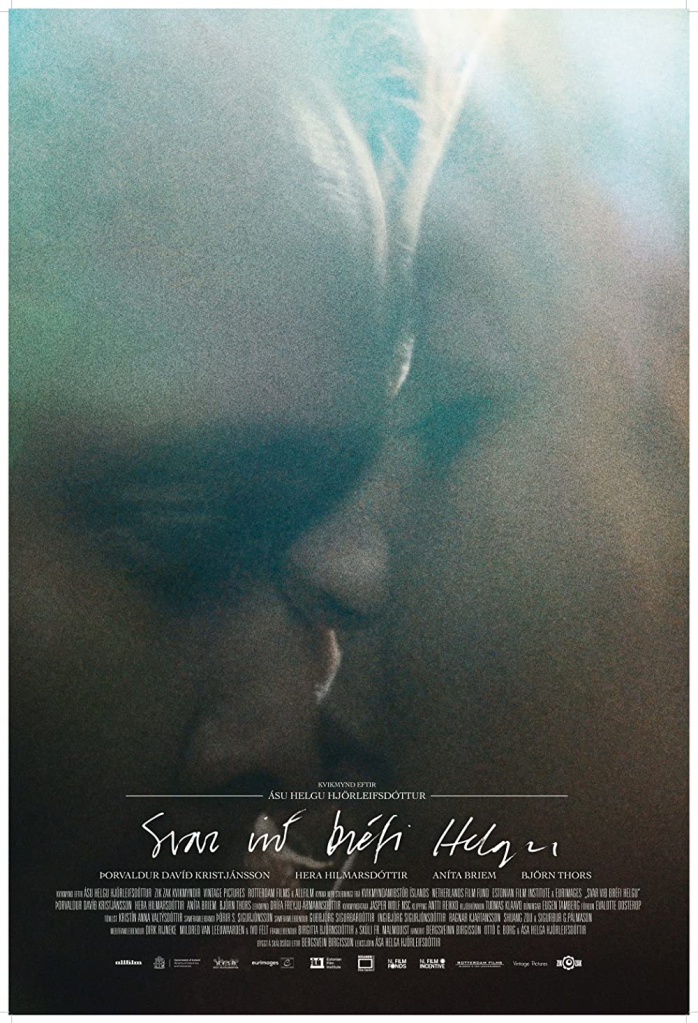

A Letter from Helga (Dir. Ása Helga Hjörleifsdóttir)

A Letter from Helga is a very slow film, and while that’s not a death knell for me – many of my favorite films would qualify as slow cinema – If you can’t create the right mood the slowness becomes boring. Unfortunately, Ása Helga Hjörleifsdóttir’s latest outing falls into the boring camp.

★★½

Le Coyote (Dir. Katherine Jerkovic)

A man agrees to take on the son of his heroin addicted, estranged daughter while she goes to rehab in this quiet, understated film. Very slow and very quiet to the point of it being distracting watching at home as pat of SIFF’s virtual festival.

★★

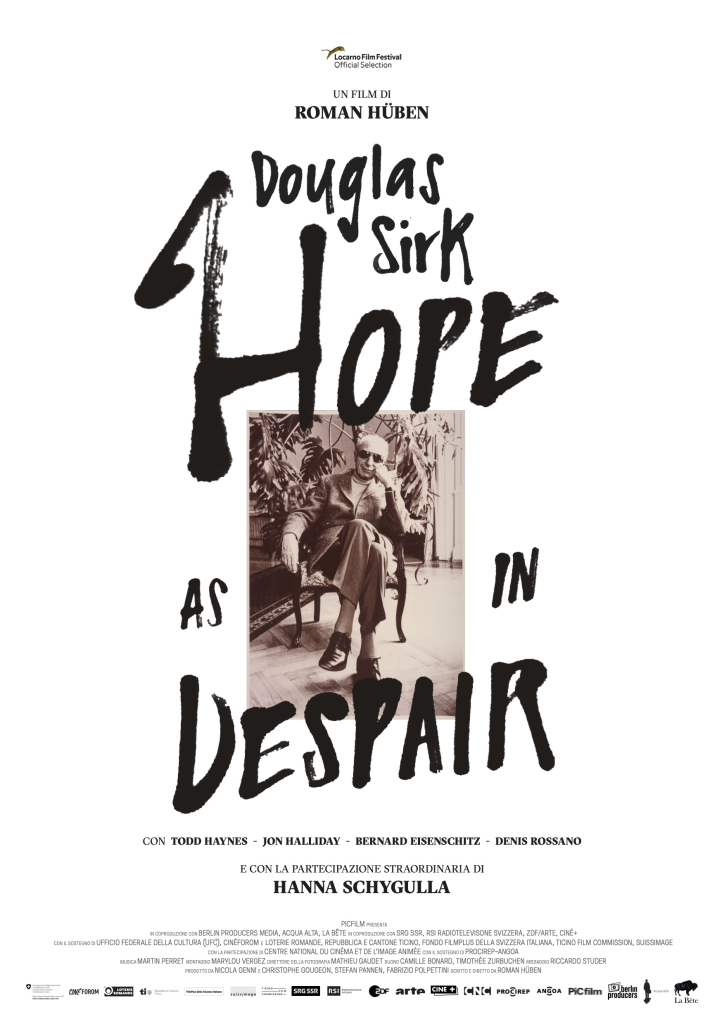

Douglas Sirk – Hope as in Despair (Dir. Roman Huben)

An extremely dry documentary about the renowned melodrama filmmaker, Douglas Sirk. I love Sirk and am interested in learning more about him, but even with that I struggled to pay attention to the film it was so barren of style.

★½

Snow and the Bear (Dir. Selcen Ergun)

In a part of Turkey where winter never seems to end a nurse Aslı (Merve Dizdar) arrives in a small town where the local doctor is unable to reach and begins her compulsory service. The film is a perfect watch on a scorching hot summer day as director Selcen Ergun captures the cold in a way that will chill anyone to the bone.

★★★

20 Days in Mariupol (Dir. Mstyslav Chernov)

Horrific and gruesome, 20 Days in Mariupol uses its unprecedented access to war torn Ukraine to create a moving documentary. That said, outside of proximity, the documentary doesn’t bring anything new to the medium. Still a miraculous story to tell.

★★★