In flipping The Brutalist roles with her husband Bradey Corbet, Mona Fastvold creates a feminine take on America’s poisonous soul that destroys creative or enlightened immigrant when they attempt to place roots here. While Corbet’s turn to direct focused on a fictional architect who felt convincingly real to the extent that many people questioned if he was, Fastvold’s The Testament of Ann Lee depicts a real person who feels too fantastical to believe.

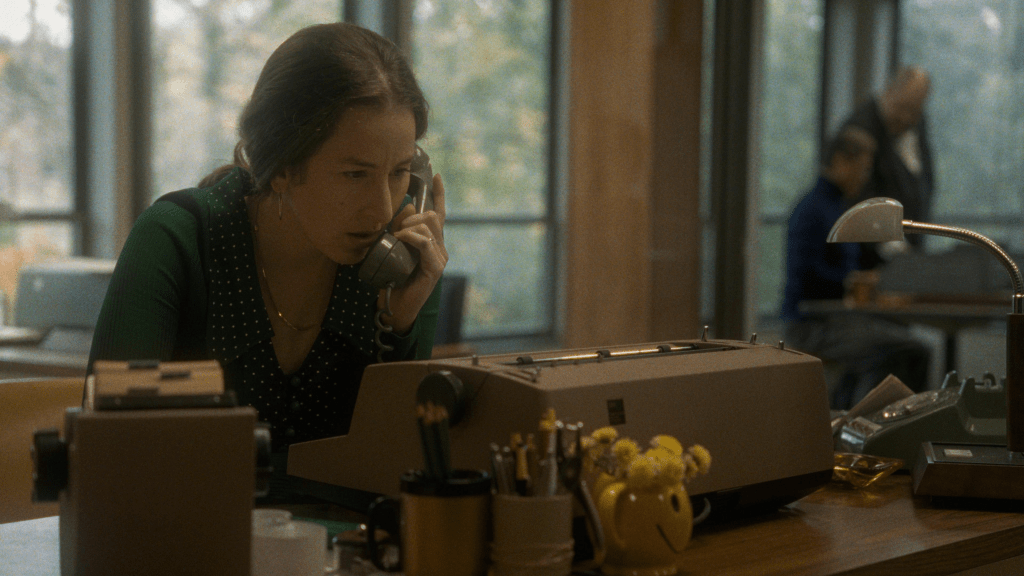

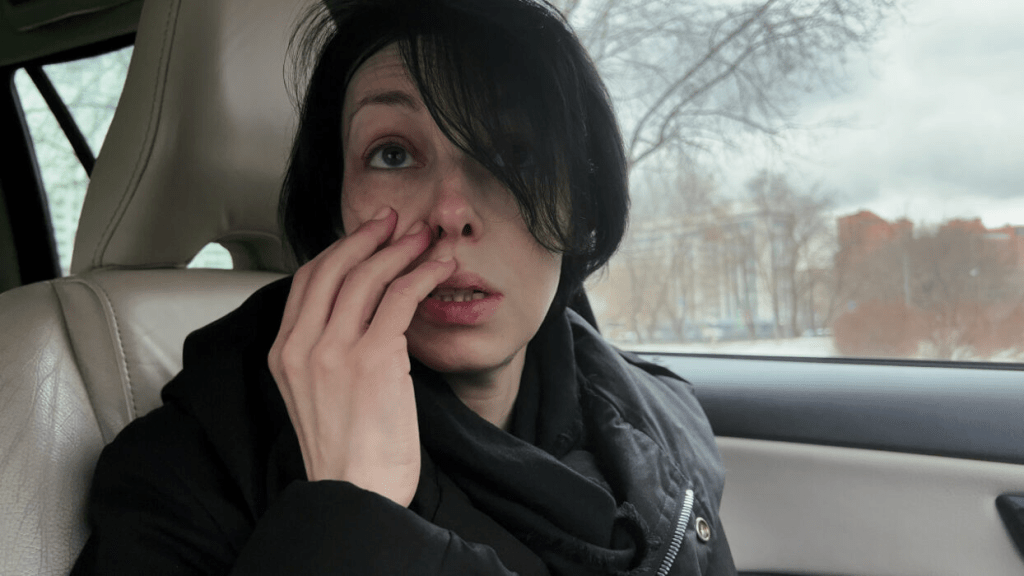

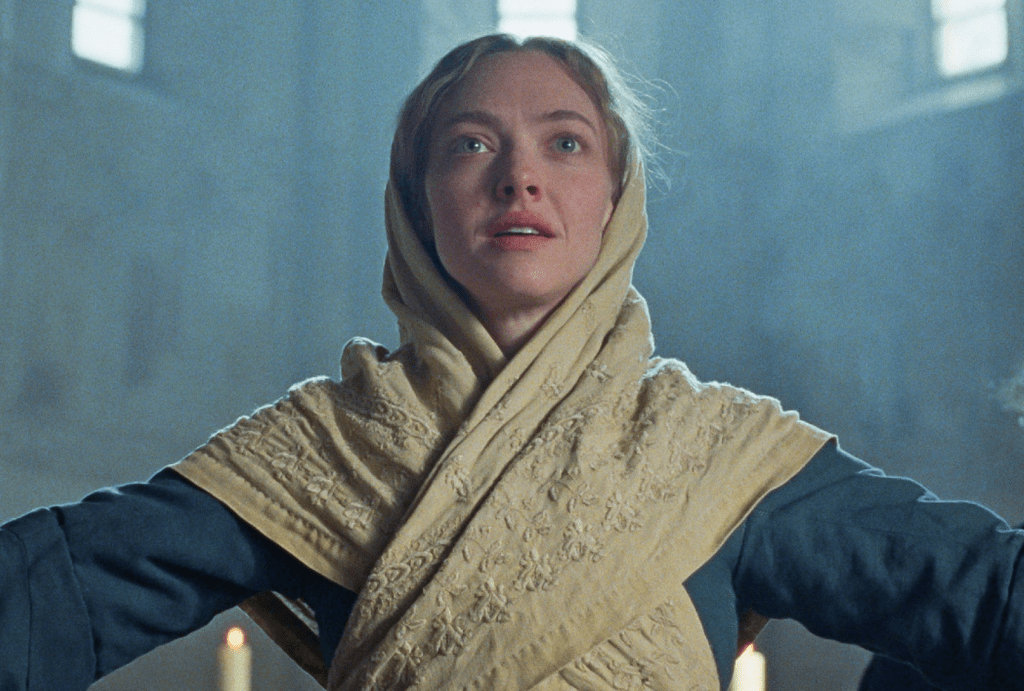

Amanda Seyfried plays the titular religious leader as a wide-eyed, curious, and approachable mother to her congregation. Despite her position atop the Shaker movement and the proclaimed second coming of Jesus Christ she doesn’t seek power, has no interest in controlling her followers for personal gain, and truly only wants to spread her beliefs and visions for the benefit of others. While some may criticize Ann Lee’s perpetual purity as the film lacking character development in its protagonist, in my opinion, that was not Fastvold’s goal. The film is less about the life of Ann Lee and instead about the bliss that she brings her believers as well as the world’s refusal to allow something so pristine and genuine to exist.

The Testament of Ann Lee takes no definitive position on the woman and the Shaker’s position that she was the rebirth of the messiah, though I have seen some critics impose their own assumptions of this crux of the film. While I assume that Fastvold is not personally a Shaker with those beliefs – the film’s credits inform that the Shaker movement is down to only two current believers – but to Fastvold’s purpose Ann Lee is a perfect symbol of the good in humanity for contrasting against the rigid and unaccepting world.

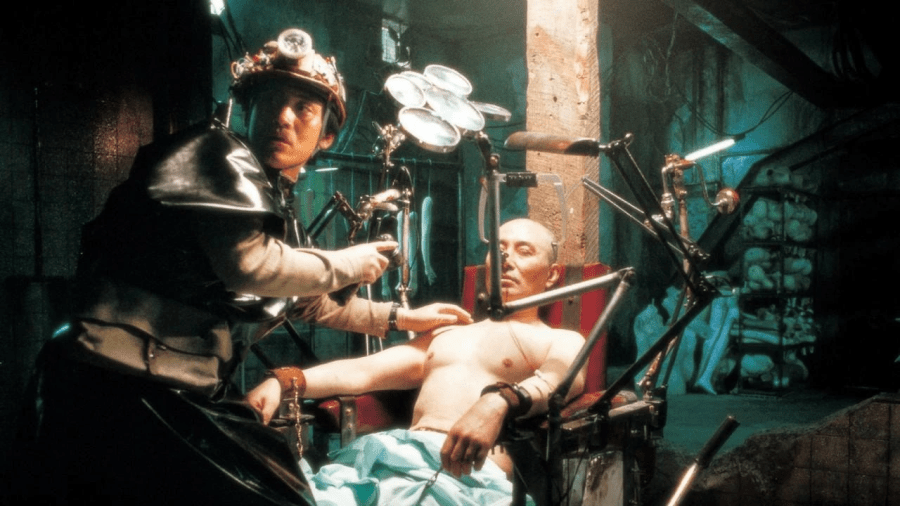

Not only does Ann Lee represent a purity which the patriarchal world she was a part of, that we still are a part of, feels compelled to destroy. It instinctively despises and uproots such a feminine ideal before it can spread or thrive. This femininity is not solely expressed by the gender of the film’s protagonist – though the 18th century Sharkers not only allowing women to preach but lead their church was a level of progressive feminism that it would take literal centuries to return – it is also expressed in the filmmaking. The Brutalist shot in gorgeous 70mm was a feast for the eyes though as the title implies, the views were rather brutal with lots of harsh lighting clearly showing every inch of László Tóth’s architecture. The Testament of Ann Lee was also shot in 70mm, yet it has a completely different feel to it. Instead of the harsh lights that consume the former’s film, Fastvold’s picture is lit with warm candlelight and creates a much more welcoming demeaner.

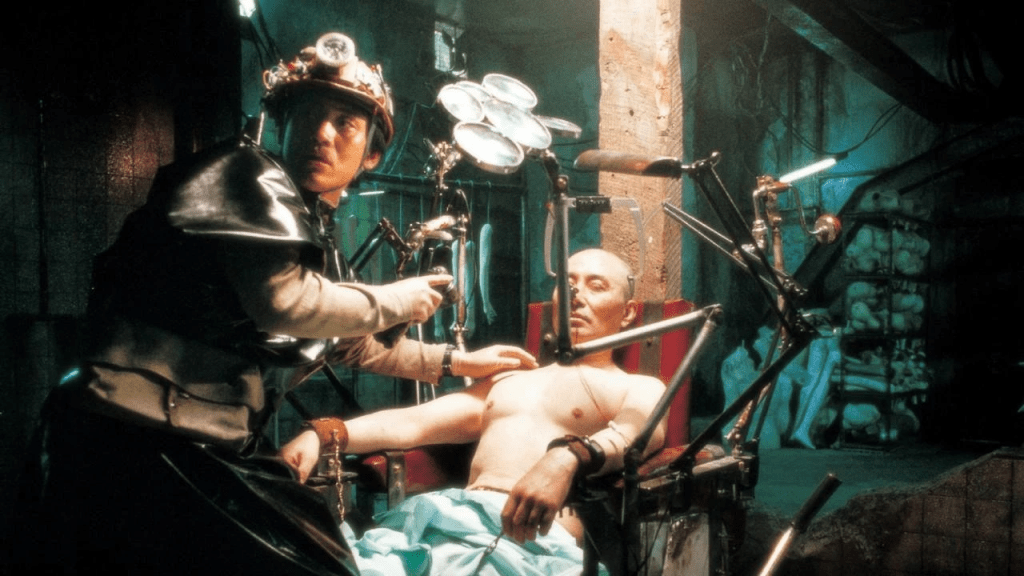

Though arguably the directorial decision that marks the film as the feminine alter ego of The Brutalist is that it is a musica, though not a traditional one. The film is peppered with the Shaker’s worship sessions, all of which include music and dance. Celia Rowlson-Hall’s choreography for the film is brilliant as different worships flow from improvisational (at least in appearance) to showy structured moments flawlessly. While the scene scored to “Worship” shows this fluidity the clearest, the “All is Summer” prayer on the boat to America is the standout. Fastvold uses Rowlson-Hall’s choreography with cuts between seasons to create a mesmerizing, singular number.

In addition to Rowlson-Hall’s choreography, these musical and dance moments fully succeed because of the contributions by composer Daniel Blumberg who is fresh off his Oscar win from, as one might guess, The Brutalist. His score uses the bones of actual Shaker hymnals to create the soundscape that floods the majority of the film. He taps into the inherently rhythmic essence of the Shaker’s prayers to propulse the film forward. Each individual aspect of The Testament of Ann Lee builds it into a pure cinematic experience. Blumberg’s score, Rowlson-Hall’s choreography, William Rexer’s cinematography and Fastvold’s direction all blend together into a singular piece worthy of one of the Shaker’s three-day marathon prayer partie