Grand Prix winner (second prize) at Cannes this year was the Indian film All We Imagine as Light, and it was easily the best of the big three award winners (Emilia Pérez was the Jury Prize winner and Anora won the Palme). While being produced in India, don’t expect any fantastical action or musical numbers as is common with Bollywood fare. Payal Kapadia’s film instead has more in common with a US independent film than the studio system in her country.

The film centers on roommates and nurses at the same hospital in Mumbai, Prabha (Kani Kusruti) and Anu (Divya Prabha) and their relationships. Prabha as the senior of the two women, has been married for years, but her husband has been working and living in Germany for quite a while and his calls have become less and less frequent. At the beginning of the film, it has been over a year since they’ve talked, but out of the blue he sends her a high-end rice cooker in the mail without so much as a letter. This brings her relationship or lack thereof to the forefront of Prabha’s mind.

Anu’s love life differs greatly from that of Prabha’s, but is no less complicated. She is in a relationship with a Muslim man Shiaz (Hridhu Haroon). The cultural difference between the two means they must keep their relationship a secret, though their success at that is questionable as their relationship is the subject of gossip between the nurses at the hospital. Compounding on this is that her parents are constantly sending her pictures of Hindi men that they are trying to marry her off to.

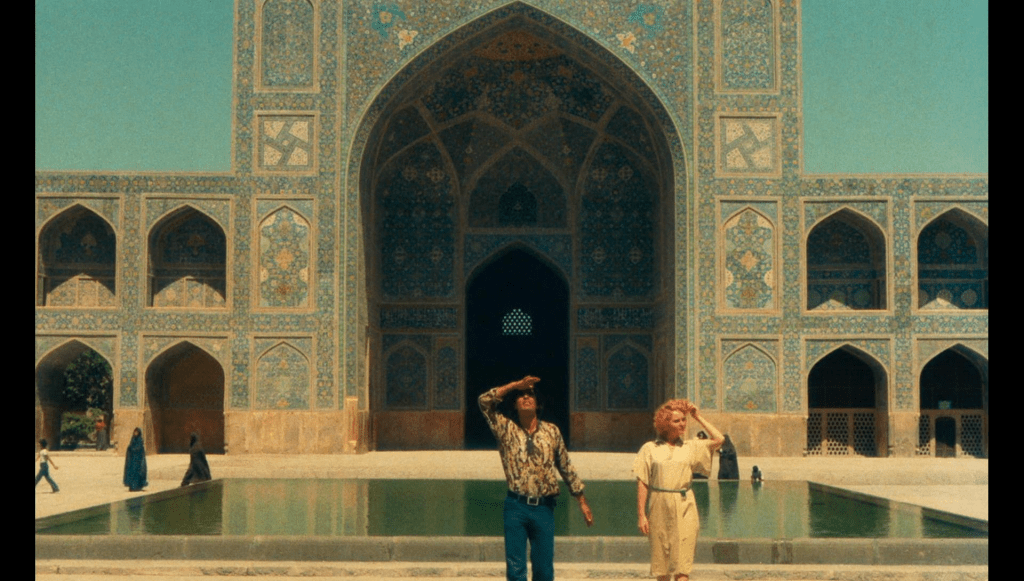

The final plot line in the film follows Parvaty (Chhaya Kadam) a cook working at the same hospital as Prabha and Anu. She is being evicted from her home of 22 years by a predatory building company since she has no papers after the loss of her husband. Eventually she succumbs to the pressure from the builders and returns to her small village far from Mumbai with the help from Prabha and Anu where the second half of the film takes place.

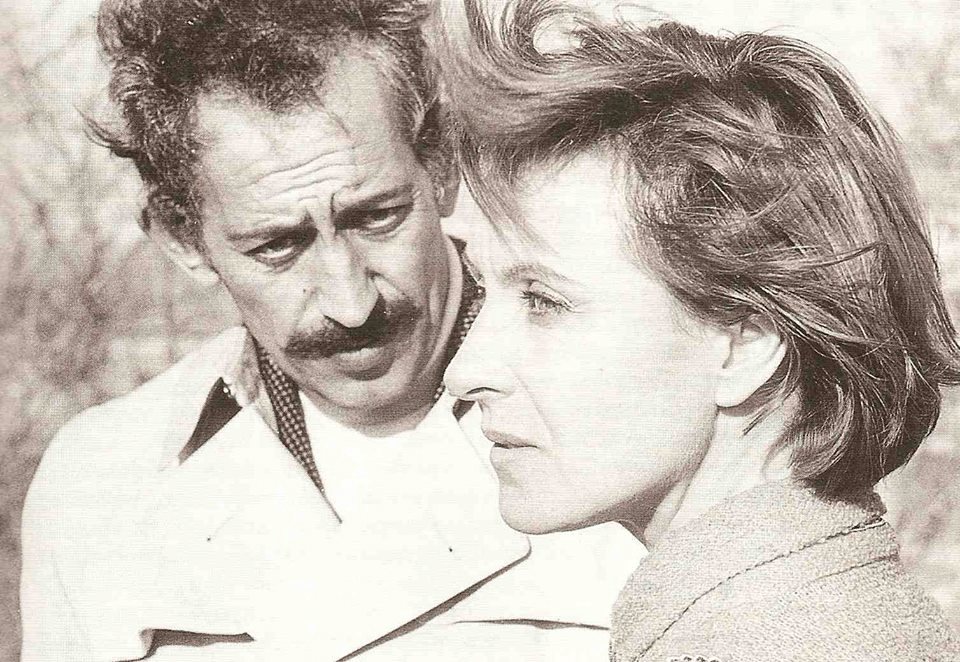

The beauty of the film is in the intimacy of both the relationships and the camera work. Cinematographer Ranabir Das holds tight on faces and hands to tell the story of how each character feels about the other. These close ups rely heavily on the actors to have perfect control over their facial expressions, and they live up to the expectations.

This intimacy is also expressed in the screenplay. Written by the director, Kapadia touches on both the day-to-day livings of her female protagonists as well as the major, or major to the characters, relationships with men. This blending of events makes the characters feel real and their experiences true to life. The lives of the characters feel lived in and personal, inducing empathy from the audience.

Intimate stories of women’s lives often get the short shrift in the film industry, especially in areas of the world where women have fewer rights, but Kapadia works against the system to create something special. Cannes missed out on having unprecedented back-to-back female filmmakers win the Palme as All We Imagine as Light is a perfect film.