In search of a contrast from yesterday’s extravagant blockbuster I needed to return to my independent roots with one of my favorite directors working today, Kelly Reichardt, for her new film The Mastermind.

Reichardt, known for her deliberate pace making her one of the current flag bearers for slow cinema, once again takes her turn in a genre of cinema that seems antithetical to her style. The Mastermind does for heist films what Night Moves did for ecoterrorist pictures, and Meek’s Cutoff did to the neo-western. In all three of the films, she deconstructs the genre removing it of all the glitz that normally attracts an audience and instead focuses on the characters and the impact that the inciting incident of the film has on their psyche.

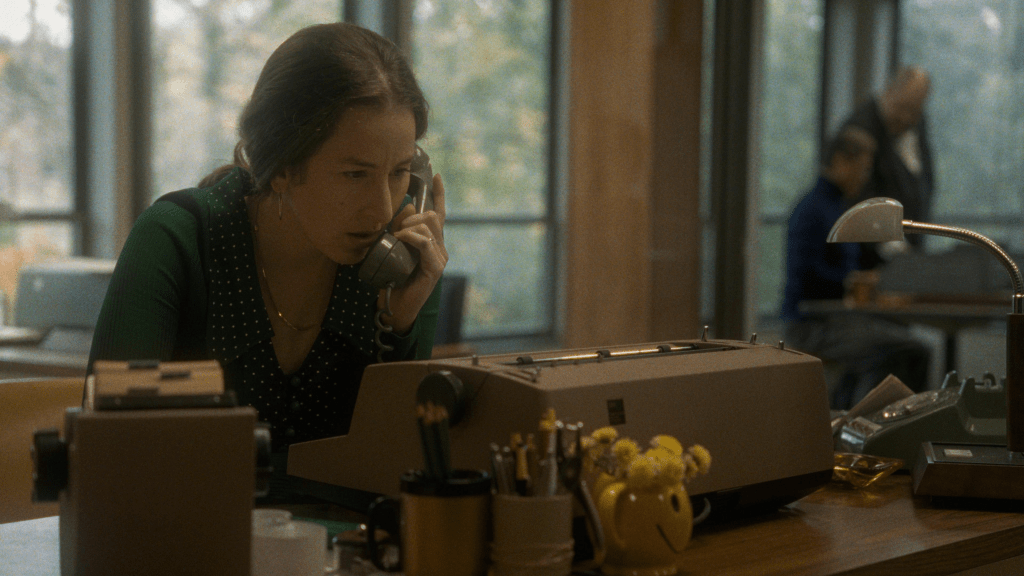

James Mooney (played magnificently by Josh O’Connor) is a failed architect who feels emasculated by his parents Bill (Bill Camp) and Sarah (Hope Davis) who degrade him for being without work, and his wife Terri (Alana Haim whom I wish we saw more of), who provides for him and their two children. As an avid art connoisseur, James plans to steal four paintings from the museum with the help of a few friends. While the heist is initially successful, it is quickly pegged to James, and he is forced to leave his family and go on the run. While this seems like it would be a tense setup for a thriller, Reichardt does not focus on the active tension, but instead sits with Mooney as he comes to terms with his new reality.

O’Connor plays the part of James as a lost soul who feels entitled to a life without working for it. He feels no drive to return to architecture but instead poorly plans a heist that is only initially successful because of security guards caught in a complete malaise and one of the people he hired to help with the heist brandishing a gun despite James asking him not to bring one. His entitlement around the theft is shown both by his borrowing money to pay his accomplices for the heist from his mother, and by his reaction upon having the stolen paintings in his possession. While his intension is to sell the paintings, he initially hangs them on his wall as if they should be his rather than in a museum full of people he thinks won’t respect them. Once he is forced onto the road this entitlement persists as he endangers his friends by staying with them, and then by first asking his wife to send money and finally resorting to stealing to fund his continued escape.

Reichardt enhances this feeling of masculine entitlement through the supporting characters James meets on the run. Other men give him the benefit of the doubt and want to support him while women resent his delusion and begrudge him for thinking they should help him. Additionally, the background of the setting (1970 America) calls out James’s privileged stance by including news footage of the time focusing on the terror that was the Vietnam War, and eventually this movement for peace and equality literally engulfs him to diminish his self-aggrandizing beliefs.

Reichardt has always been interested in gender dynamics, and she holds no punches in her takedown of masculine entitlement in The Mastermind. While the film is rather vicious in its subtext, it still manages to maintain that essential Reichardt calmness. She is not looking to spoon feed plot nor themes to the viewer, but instead she trusts that by using a well-known genre as a backdrop and filling it with contemplative moments an attuned audience is able to process the message behind the silence.